3. Establishing the Facts

The Committee establishes the following facts on the grounds of the literature and archival research that was conducted in case RC 3.162 and in this reconsideration case and that involved bodies and individuals in the Netherlands, Germany, Israel, the United States and elsewhere.

The Stern-Lippmann family: Margarethe and Siegbert Stern-Lippmann and their four children

Johanna Margareta Lippmann was born on 6 January 1874 in Berlin. She married Samuel Siegbert Stern (1864-1935), who, like herself, was of Jewish descent and was a co-owner of the textile business Graumann & Stern. The couple lived in Babelsberg, now a district of Potsdam, and had four children: Annie Regina Stern (1899-1989), Hilde Sophie Stern (1901-1984), Hans Martin Stern (1907-1953) and Luise Henriette Stern (1909-1944). In 1924 Annie Stern married the Dutch merchant and art dealer James Vigeveno. In 1927 her younger sister Hilde married met Otto Liebstaedter, a book dealer of German Jewish descent. Son Hans Stern married Rosa Marie Czellitzer, the daughter of a Jewish ophthalmologist from Berlin. In 1934 the youngest daughter, Luise, married Herbert Hayn, a clothing manufacturer also of German Jewish descent

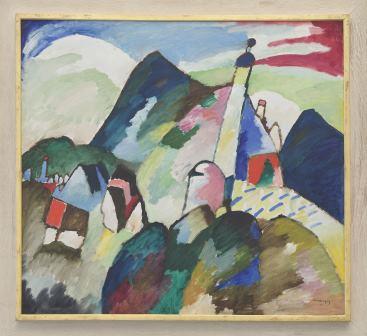

Mr and Mrs Stern owned a substantial art collection. A will drawn up by or for the couple in 1924 refers to 144 numbered objects and artworks, including over 100 paintings and drawings. One painting by Kandinsky, designated as ‘Landschaft’ [‘Landscape’], is mentioned in this will. The Applicants submitted a copy of a transcript of a typescript of this will, on which it is stated: ‘Verkündet am 14. Oktober 1935’. [‘Proclaimed on 14 October 1935’.] This means that the will was opened on the said date, after the death of Siegbert Stern, by a judicial authority and proclaimed valid.

It is not known when the Sterns purchased the painting by Kandinsky. A part of the couple’s collection can be seen in an album containing photographs of the interior of their home in Babelsberg. One of the photographs in the album is of a room with two paintings on the wall, one of them being the said work by Kandinsky. Further artworks can be seen in other photographs, including the painting The Circumcision, about which the Committee advised in case RC 1.44. A photography expert who examined the album at the request of the Committee concluded that the album was compiled between around 1915 and 1940. According to the photography expert, it is not possible to give a more precise dating for the photograph in which the work being claimed be seen.

Persecution of the family and flight from Germany to the Netherlands in the 1933-1938 period

After Hitler came to power in January 1933, the existence of the Sterns and their children became increasingly threatened because of their Jewish descent. Hilde Liebstaedter-Stern and Luise Hayn-Stern and their husbands left for the Netherlands immediately in 1933. Their father, Samuel Siegbert Stern, died in Berlin in August 1935. Annie Vigeveno-Stern and her family fled to the Netherlands the following year. The Stern children urged their mother to emigrate too because she was being harassed by the Nazis. Her private chauffeur Erich Stritzke, who had worked for the Sterns since 1925, stated the following after the war: ‘Frau Stern war in dem kleinen Ort Babelsberg sehr gut bekannt und erfreute sich, da sie als wohlhabend galt, der unangenehmsten Aufmerksamkeit der Nationalsozialisten.’ [‘Mrs Stern was very well known in the small community of Babelsberg and was happy there. She was at the receiving end of the most unpleasant attention of the National Socialists because she was considered wealthy.’]

Margarethe Stern-Lippmann left Babelsberg in the spring of 1937 and settled in the spa town of Badenweiler in Southern Germany. She took a small proportion of her possessions with her when she moved. Persecution of the Jews became even worse during the course of 1938 and she fled to the Netherlands via Switzerland. Initially she stayed with her daughter Annie and her family in Bloemendaal. In 1938 Hans Stern also fled to the Netherlands with his wife and children.

Meanwhile, from Switzerland, Margarethe had instructed Konstantin Balaszeskul, a Berlin tax advisor, to act as her authorized agent and take care of her financial affairs in Germany, including managing and liquidating her assets. This was a complex task because the Nazi authorities were keeping a close eye on the possessions of Jewish emigrants. Balaszeskul sold off the property, including the mansion in Babelsberg, which was finally sold on 2 November 1940. He also arranged to have the household contents moved to the Netherlands. In order to obtain permission for this from the German authorities, Balaszeskul had to submit an inventory and provide an opportunity for the goods to be inspected. A number of gold and silver objects were removed from the household effects because they had to be surrendered on the grounds of anti-Jewish measures.

The household contents were probably moved to Amsterdam in December 1939. Four lists of possessions were found. An entry on one list refers to 38 ‘Bilder’ [‘Pictures’], while another mentions ‘1 Ölbild’ [‘1 oil painting’] in the ‘Groβes Wohnzimmer’ [‘Large living room’]. It also emerges from the documentation that after December 1939 Balaszeskul sold two paintings by Fidus (pseudonym of Hugo Höppener) and Max Pechstein and eight sculptures for Margarethe Stern-Lippmann.

The fate of Margarethe in the Netherlands until her deportation to Auschwitz

According to the haulage company’s invoice, the household effects were sent to ‘Amsterdam – Doklaan’. It is not clear which paintings were shipped and where they ended up. It is not possible to rule out the possibility that some paintings came to the Netherlands separately from the household effects.

Margarethe Stern-Lippmann was registered as living at various addresses in Bloemendaal and Amsterdam during the 1938-1940 period. In the autumn of 1940 Margarethe moved to Hilversum, where she once again lived at several addresses, including Wernerlaan 30.

The Nazi regime declared Margarethe Stern-Lippmann stateless in 1941. In that same year she tried to obtain an emigration visa for herself and her family. Part of this process involved putting the painting Portrait of Miss Edith Crowe by Fantin-Latour at the disposal of the Dienststelle Mühlmann (Mühlmann Agency), a German organization that acquired works of art for Germany. This painting was not in Margarethe’s collection. She bought it at the end of 1941 especially for this purpose from the D’Audretsch art gallery in The Hague for NLG 40,000. The German Jewish art dealer Myrtil Frank was an intermediary in this purchase. During the 1941-1942 period he lived within walking distance of Margarethe’s residence in Wernerlaan in Hilversum. Frank handed over the painting to the Mühlmann Agency but the emigration visa was never issued to Margarethe.

Information discovered in archives reveals that in the 1941-1942 period Myrtil Frank was also involved in various sales, or attempted sales, of artworks from Margarethe’s collection, including paintings by Anton Mauve, Jacob Jordaens and Lovis Corinth.

In 1942 or 1943, during the German occupation, Margarethe went into hiding in Bussum at the home of the actor and theatre manager Johan Brandenburg and his wife Cornelia (Corry) Vuijk. Margarethe was betrayed and arrested there on 27 April 1944. She was imprisoned in Amsterdam and ten days later was transported to Westerbork transit camp, where she, being a ‘criminal’, was incarcerated in the penal barracks. She was deported to Auschwitz on the first available train and was murdered virtually immediately after her arrival.

Fate of Margarethe and Siegbert’s children in the Second World War

Their daughter Luise and her husband Herbert Hayn also became victims of the persecution of the Jews. Their little daughter Doris survived while in hiding. Hilde and Otto Liebstaedter-Stern and their daughters Marla and Hedi also survived while in hiding in Nunspeet, where they were domiciled, and elsewhere. Hans and Annie and their families were able to escape to the United States in time.

Hilde Liebstaedter-Stern wrote the following to a friend shortly after the liberation:

‘Von unserer ganzen grossen holländischen Familie sind Otto, ich, Marla, Hedi als einzige übrig geblieben. … Meine Mutter war in Bussum geschuild, ist auch im apr. 44 gepackt. Meine Schwester u. Schwager waren erst in Vugt, sind dann nach Auschwitz gekommen. All meine Tanten, Onkels, Vettern sind verschleppt. Ihr besieht, wie einsam es um uns geworden ist …. Dass Ottos Mutter in März 43 nach Westerbork gekommen ist, wisst Ihr wahrscheinlich. Sie ist seit dem auch verschollen. … Otto ist so mager geworden, dass Ihr ihm kaum erkennen werdt, aber sonst gut im Stande, und wir haben alle sehr viel in dieses Zeit gelernt. … Wir wollen vorlaufig in Nunspeet bleiben u. hoffen, in ca. 4 Wochen ein eigenes Haus zu beziehen.’

[‘Out of our entire big Dutch family, Otto, I, Marla and Hedi are the only ones left. … My mother went into hiding in Bussum, but was also arrested in April 44. My sister and brother-in-law were first of all in Vugt, but then they were taken to Auschwitz. All my aunts, uncles and cousins were deported. You can see how lonely it has become for us …. You probably know that Otto’s mother was taken to Westerbork in March ’43. She’s been missing since then too…. Otto has become so thin that you would hardly recognize him, but otherwise he is well, and we all learned a lot during those days…. We want to stay in Nunspeet for the time being, and we hope to move into a home of our own in about 4 weeks.’]

Was ‘Blick auf Murnau mit Kirche’ a part of Margarethe’s estate after the Second World War?

It is not clear what happened to a large part of Margarethe’s art during the Nazi era. When she fled to the Netherlands in 1938, she was not able to take all her possessions with her and she had to sell artworks at around that time. She also sold works of art during the German occupation of the Netherlands.

After the war, the family made attempts to get back artworks that they deemed to be missing, as can be seen, for instance, from declaration forms at the Netherlands Art Property Foundation (hereinafter referred to as the SNK).

Starting in 1950, Margarethe’s descendants concentrated primarily on sharing out the art she owned that they assumed was still present (in Amsterdam and Nunspeet). As the only children and/or children-in-law still living in the Netherlands, Otto and Hilde Liebstaedter-Stern played an important part in this. The new material submitted by the Applicants makes it clear that the other children and/or children-in-law were also closely involved in dividing up the art. The picture that emerges from the documents is one of a family whose members were getting on well with each other and were trying to reach a harmonious settlement of the estate. Fritz Martin (Fred) Stern, a nephew of Siegbert Stern who lived in New York, acted as executor.

Until June 1952 the descendants assumed that the painting ‘Blick auf Murnau mit Kirche’ – which they referred to as ‘Landschaft’ [‘Landscape’]– was part of the undivided estate. This emerges from the following documents:

• At some point between May and October 1950, Hilde’s husband Otto Liebstaedter drew up a list of ‘Kunstgegenstaenden aus Holland’ [‘Art objects from Holland’]. He did this at the request of his sister-in-law Annie, who sent him a copy of the will to that end from the United States, and Hilde asked for ‘a complete list of the things which they still have in Holland, as well as the objects which have been sold by them’. Otto’s original list, which was probably handwritten, has not survived, but in 2019 the Applicants found a typed copy that was in the possession of descendants of Fred Stern in the United States. There are forty ‘Bilder’ [‘Pictures’], including the ‘Landschaft’ [‘’Landscape’] by Kandinsky, and nine sculptures on Otto’s list. He noted: ‘Ich habe verkauft bei Anne J. Olthoff für fl. 1990.- / nur keine Bilder’. [‘I sold works at Anne J. Olthoff for NLG 1990.- / just no pictures.’] He added: ‘Ich hoffe, dass es so gut ist’. [‘I hope I did the right thing.’] Eleven of the said paintings were in the Stedelijk Museum and in the Associatie Cassa building in Amsterdam. A letter by Otto during this period states that approximately thirty paintings were in his home in Nunspeet or ‘bei Freunden untergebracht’ [‘with friends’]

• On 29 October 1950 in the United States James Vigeveno drew up a ‘Bilderliste mit Preisschaetzungen’ [‘List of pictures with estimated prices’] on the basis of Otto’s list. It contains all the works mentioned by Otto but now with prices. James also underlined a number of works in red. Kandinsky’s ‘Landschaft’ [‘Landscape’] was among the works underlined in red. Its price was given as 500 dollars. Annie Vigeveno explains the additions in a letter of 29 October 1950 to executor Fred Stern: ‘Regarding the pictures, we are giving you enclosed an estimate of the values of the paintings from Otto’s list, and would strongly advise to have those with the red marks come to this country – either for sale or distribution among the heirs.’ In her letter Annie also mentions that she will send a copy of the ‘Bilderliste mit Preisschaetzungen’ [‘List of pictures with estimated prices’] to her brother Hans Stern.

• At the beginning of 1952 the family decided to have all art works valued by the Amsterdam art dealer and valuer Bernard Houthakker for the purposes of settling the estate. In view of this on 4 February 1952 executor Fred Stern wrote to Otto Liebstaedter as follows: ‘Ich schicke Dir also noch eine Kopie der wahrscheinlich vollstandigen Liste die ich im Oktober 1950 von James erhalten habe in zwei Exemplaren, damit Du sie als Grundlage benuetzen kannst.’ [‘So I am sending you a copy of what is probably the complete list, two copies of which I received from James in October 1950, so that you can use them as a basis.’] What Fred Stern called ‘wahrscheinlich vollstandigen Liste’ [‘probably the complete list’] refers to James Vigeveno’s ‘Bilderliste mit Preisschaetzungen’ [‘List of pictures with estimated prices’] of 29 October 1950 (which also includes Kandinsky’s ‘Landschaft’ [’Landscape’]).

Kandinsky’s ‘Landschaft’ [’Landscape’] is not on the lists of the undivided estate that were amended or drawn up from June 1952:

• In June 1952 Houthakker valued the works present in Nunspeet. A copy – newly typed because it was composed differently – of James Vigeveno’s ‘Bilderliste mit Preisschaetzungen’ [‘List of pictures with estimated prices’] was found in his records. There are handwritten notes on this copy. For example, alternative prices are written alongside James Vigeveno’s earlier estimates and Kandinsky’s ‘Landschaft’ [’Landscape’] has been crossed out. According to a handwriting expert brought in by the Applicants, the handwritten prices were noted by Houthakker, as were a few other comments. It is plausible that Houthakker was also the person who crossed out Kandinsky’s ‘Landschaft’ [‘Landscape’] on this copy.

• On 18 September 1952 Houthakker drew up an ‘expert’s certificate’ about 37 paintings, ‘alle behorende tot de nalatenschap van Mevrouw M.J. Stern-Lippmann en zich bevindende in diverse percelen te Nunspeet (Gld.) en te Amsterdam in het Stedelijk Museum en in het gebouw van de Associatie Cassa’ [‘that all belong to the estate Mrs M.J. Stern-Lippmann and that are present in various properties in Nunspeet (Gelderland) and in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and in the Associatie Cassa building’]. Kandinsky’s ‘Landschaft’ [‘Landscape’] is not on this certificate either.

• The estate was distributed among the heirs in 1954. Kandinsky’s ‘Landschaft’ [’Landscape’] is not mentioned on the distribution list.

• In 1955 J.P. Barth and Dr W.H.C. Schukking, financial and legal advisors to the family, prepared an overview of artworks in the estate ‘welke na 1945 niet meer in de boedel werden aangetroffen’ [‘that were no longer found among the household contents after 1945’]. Kandinsky’s ‘Landschaft’ [‘‘Landscape’] is not on this certificate either. Barth and Schukking sent this overview (hereinafter referred to as the Schukking list) to the SNK in 1955 and, in a slightly amended form, to the German authorities in 1958 and 1959.

The family was not sure of the extent of the estate until after Houthakker’s valuation in June 1952. In his 1950 ‘Liste von Kunstgegenstaenden aus Holland’ [‘List of art objects from Holland’] Otto Liebstaedter remarked: ‘Ich hoffe, dass es so gut ist’. [‘I hope I did the right thing.’] In his letter of 4 February 1952 to Liebstaedter, executor Fred Stern refers to the James Vigeveno’s ‘Bilderliste mit Preisschaetzungen’ [‘List of pictures with estimated prices’] as ‘wahrscheinlich vollstandigen Liste’ [‘probably the complete list’]. Spaces in Otto’s list where titles are supposed to be also point to this uncertainty. The Committee concludes from these and other indications that Otto prepared his 1950 list on the basis of the will and his own memory and that he did not himself see the artworks stored ‘in diverse percelen’ [‘in various properties’] after the war. Houthakker, on the other hand, travelled to Nunspeet in connection with valuing the artworks in order to inspect all the works still belonging to the collection.

December 1951: the museum buys the work from Legat. The museum’s inventory card

Research has revealed that the museum purchased the work in December 1951 for NLG 11,500 from the art dealer Karl Legat, who was of Austrian origin and was based in The Hague. The work is known in the museum as Blick auf Murnau mit Kirche.

The museum prepared a handwritten inventory card with the following provenance information: ‘Légat, Den Haag (1951) fl. 11.500-’ / ‘Vroeger verzameling A. Kaufmann; door diens in Nederl. wonende dochter verkocht Légat. (opg. Légat)’. [‘Légat, The Hague (1951) NLG 11,500-’ / ‘Previously the collection of A. Kaufmann; whose daughter living in the Netherlands sold it to Légat. (stated by Légat)’] On the grounds of museum correspondence and various dates on the card, it is plausible that this information was added after September 1953, and possibly not until 1955. This was after Legat died on 20 July 1953. In a letter of 30 October 1951 to Eindhoven City Council, in which the museum asked the City Council to purchase the work from Legat, the museum reported that: ‘Intussen is echter komen vast te staan dat de kunsthandelaar het schilderij voor F. 10.000 heeft gekocht.’ [‘It has meanwhile become known however that the art dealer bought the painting for NLG 10,000.’]

Investigation into A. Kaufmann

The Committee asked the ECR to conduct an investigation into A. Kaufmann because the museum’s inventory card states that the work had been part of A. Kaufmann’s collection and that his daughter, who lived in the Netherlands, sold the work to Legat. Three people with the name A. Kaufmann or A. Kauffmann emerged during the ECR’s investigation.

The first is the German Jewish art dealer and collector Arthur Kauffmann (1887-1983). The ECR approached a son of his, who is an art historian. He stated that his father was probably not the person referred to on the museum’s card: ‘He was a refugee from Germany who settled in London in 1938. Having been an art auctioneer in Frankfurt (Hugo Helbing), he became an art dealer in London. I do not think that he had close links with Dutch dealers in 1951 and he certainly did not have any daughters.’ He also wrote: ‘… I do not think that my father privately owned a Kandinsky painting before 1951.’

The ECR found out that the second person, the French Jewish draughtsman Albert Kaufmann (1903-1987) also had no connections with the Kandinsky, the Netherlands, Legat or the Stern family.

With regard to the third person, the Düsseldorf artist and art collector Arthur Kaufmann (1888-1971), the ECR’s investigation revealed that he did have such connections. This Kaufmann owned an art collection and was an admirer of Kandinsky. He had a son and a daughter. He lived in the Netherlands for a few years starting in 1933. From a social and geographic point of view, Arthur and his wife Lisbeth were close to the art dealers Karl Legat and Myrtil Frank and the children of the Stern family who had settled in the Netherlands. They were all members of the German Jewish refugee community and knew one another, be it directly or via family members or friends. The sources of and about Arthur Kaufmann consulted by the ECR contain no indications that he had owned a Kandinsky. The Kaufmann family soon left the Netherlands: Arthur in 1935, daughter Miriam in 1936 and Lisbeth and son Hans in 1937. The Kaufmann family was therefore no longer in the country when Margarethe Stern-Lippmann settled in the Netherlands in 1938.

The ECR’s draft investigation report of 24 May 2022 refers to a personal archive of Arthur Kaufmann in New York Public Library (NYPL). Because of the restrictions resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, the ECR did not have the opportunity to examine this archive. Information requests from the ECR to the NYPL did not lead to any documents being provided either.

In view of the possible importance of this personal archive of Arthur Kaufmann, two members of the Committee travelled to New York to examine that archive. In that archive they found recollections by Arthur Kaufmann’s wife Lisbeth containing information about the art collection that she and her husband had built from the nineteen-twenties onward: ‘Arthur’s studio in the New Academy [in Düsseldorf] was rather far from our home now, and when people wanted to see his work they had to visit him there, because he made it a rule to decorate the walls of our apartment only with the paintings and drawings of other artists he had started to collect. He would either buy them outright or exchange for some of his own. So we had works by Gleize, Max Ernst, Otto Dix, Jankel Adler, Seehaus, Feininger, Karl Schwesig, Theo Champion, Walter Ophey, Uzarski, and others.’ Kandinsky is not mentioned in this summary, which is all the more striking because it emerged from the sources consulted by the ECR and various documents in the New York archive that Arthur very much admired Kandinsky. Furthermore, the recollections of both Arthur and Lisbeth Kaufmann are characterized by a lengthy writing style. Arthur’s memoires alone cover more than five hundred pages. In them he describes in detail, for example, his connections with well-known artists. Yet there is no mention of the acquisition of a Kandinsky in the aforementioned quote from Lisbeth’s memoires or in other documents in Kaufmann’s archive in New York.

Picture postcard from Flory Frank in 1966

The ECR, when researching the archive of art dealer Victor D. Spark in the Archives of American Art of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, found a picture postcard that Flory Frank-Marburger sent to Spark in 1966. She was the wife of the aforementioned art dealer Myrtil Frank and a devotee of modern art. The picture on the postcard she sent is an image of Blick auf Murnau mit Kirche, and on it Flory wrote by hand: ‘This was our Kandinsky’.

Myrtil Frank – referred to above as an intermediary and dealer acting for Margarethe during the occupation – was a business partner of Karl Legat. Frank and Legat worked together closely during and after the occupation. During the war they both worked for the Mühlmann Agency, and as a result they were protected from deportation (unlike Frank, Karl Legat was not Jewish, but his wife, the photographer Meta Ehrlich, was).

Because of their German background, after the liberation Frank and Legat were faced with procedures concerning termination of their enemy status. Myrtil and Flory Frank received their declaration of termination of enemy status on 9 July 1947. They emigrated to the United States at the end of 1949. Legat and his wife Meta had their enemy status terminated on 27 April 1949. The management of their private and business-related assets by the NBI (Netherlands Property Administration Institute) ended in October 1951, in other words shortly before the purchase transaction between Legat and the museum.