3. The Facts

The Committee established the facts on the grounds of the overview of the facts and the responses to it that were received. The following summary is sufficient here.

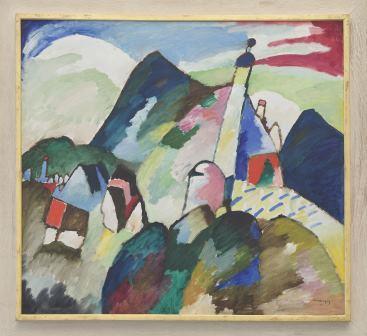

3.1 Johanna Margareta Lippmann was born on 6 January 1874 in Berlin and was of Jewish origin. She married Samuel Siegbert Stern (1864-1935), who was also of Jewish descent and among other things was an art collector. The couple lived in Babelsberg near Berlin and had four children: Annie Regina Stern (1899-1989), Hilde Sophie Stern (1901-1984), Hans Martin Stern (1907-1953) and Luise Henriette Stern (1909-1944). Mr and Mrs Stern built up a substantial art collection. This emerges, for example, from a will drawn up by the couple in 1924. It refers to 144 numbered artworks, including over 100 paintings and drawings. This will mentions one painting by Kandinsky (‘Landschaft’). The Applicants submitted a copy of a transcript of a typescript of this will, on which it is stated, ‘Verkündet am 14. Oktober 1935’. It is not known when this painting was acquired. A part of Mr and Mrs Stern’s art collection can also be seen in an album containing photographs of the interior of their residence in Babelsberg. One of these photographs is of a room in which there are two paintings on the wall, including the currently claimed work by Kandinsky. Further artworks can be seen in other photographs, including the painting The Circumcision, about which the Committee advised in case RC 1.44. According to the Applicants it is plausible that the photograph album dates from the 1933/1934 period, in any event before the death of Siegbert Stern in 1935 because he is in one of the photographs. A photography expert who examined the album at the request of the Committee concluded that the album was compiled between around 1915 and 1940. The photography expert did not give a more precise dating of the photographs on which the currently claimed work can be seen, and there is no other method available for doing so.

3.2 Samuel Siegbert Stern died on 7 August 1935 in Berlin. Stern-Lippmann moved to Badenweiler in southern Germany in the spring of 1937 in connection with the anti-Jewish measures. Stern-Lippmann took a small proportion of her possessions with her when she moved. She was also faced with anti-Jewish measures in Badenweiler, so in the summer of 1938 she fled to the Netherlands via Switzerland. A number of Stern-Lippmann’s relatives also fled to the Netherlands. Her brother-in-law Albert Stern, for instance, was registered as living in Amsterdam in March 1937 and her brother Heinrich Lippmann in June 1938. Stern-Lippmann’s children had also settled in the Netherlands in the nineteen-twenties and -thirties.

Meanwhile, from Switzerland Stern-Lippmann instructed Konstantin Balaszeskul in Berlin, whom she had appointed as her authorized agent, to take care of her financial affairs in Germany, including managing and liquidating her assets. This was a complex task because the Nazi authorities were keeping a close eye on the possessions of Jewish emigrants. Among other things Balaszeskul sold off Stern-Lippmann’s property, including the mansion in Babelsberg, which was finally sold on 2 November 1940. Prior to this sale he also arranged to have the household contents moved to the Netherlands. In order to obtain permission from the German authorities for the shipment, among other things Balaszeskul had to submit an inventory and provide an opportunity for the goods to be inspected. A number of gold and silver objects were removed from the household effects because they had to be surrendered on the grounds of anti-Jewish measures. Ultimately the household contents were transported to Amsterdam, probably in December 1939. Four lists of possessions were found concerning the shipment of Stern-Lippmann’s household effects. An entry on one list refers to approximately 38 ‘Bilder’, while another mentions ‘1 Ölbild’ in the ‘Groβes Wohnzimmer’.

3.3 Stern-Lippmann was registered as living at various addresses in Bloemendaal and Amsterdam during the 1938-1940 period. She lived with her youngest daughter Luise in Bloemendaal from 15 September 1939. According to the haulage company’s invoice that was found, the household effects that were sent to the Netherlands in December 1939 went to ‘Amsterdam – Doklaan’. It is not clear which paintings were shipped and where they ended up thereafter. It is possible that part of Stern-Lippmann’s collection came to the Netherlands outside this official household removal.

In the autumn of 1940 Stern-Lippmann moved to Hilversum, where she lived at several addresses, including Wernerlaan 30. Hermann Stern (not a relative), a merchant of German-Jewish descent who fled to the Netherlands in 1938, had lived at this address previously. In 1937 one of his two daughters, Doris, married Salomon George Kaufmann, the son of Carl and Alice Kaufmann. The name Kaufmann plays a role in the work’s provenance. No information was found, however, to show that this refers to Salomon Kaufmann or his family.

Stern-Lippmann was declared stateless in 1941. She then tried to obtain an emigration visa for herself and her family. Part of this process involved putting the painting Portrait of Miss Edith Crowe by Fantin-Latour at the disposal of the Dienststelle Mühlmann (Mühlmann Agency), a German organization that acquired works of art for Germany. This painting was not in the Stern-Lippmann collection. She bought it at the end of 1941 especially for this purpose from the firm of D’Audretsch in The Hague for NLG 40,000. The German-Jewish art dealer Myrtl Frank, who had been living in Hilversum since the beginning of 1941, was an intermediary in this purchase. Frank handed over the painting to the Mühlmann Agency but the emigration visa was never issued.

Stern-Lippmann went into hiding in Amsterdam in 1942. She was ultimately apprehended and was then deported via Westerbork transit camp to Auschwitz, where she was murdered on or around 22 May 1944. Her daughter Luise and her husband also became victims of the persecution of the Jews, as did other relatives. Her other children survived the war.

3.4 Little is known about what happened to Stern-Lippmann’s art collection during the war. Part of it proved to be still present after the liberation. Attempts were made to regain possession of artworks that were known to be missing. For example, declarations of the loss of possession of several works were made to the Stichting Nederlands Kunstbezit (Netherlands Art Property Foundation) (hereinafter referred to as the SNK). This resulted in 1949 in the restitution of only one work, the painting by Fantin-Latour referred to above. A number of individuals compiled overviews and made valuations of the Stern-Lippmann collection, for example for the purposes of dividing her estate in 1954. As part of this division a number of paintings that were still present after the liberation or had been returned to the estate were distributed among the different heirs.

The services of a number of different valuers, including the art dealer Bernard Houthakker, were used in regard to dividing the paintings. During the Committee’s investigation a number of lists of valuations of artworks were found in his archive that relate to the Stern-Lippmann art collection. On one of these lists, dated 29 October 1950 and titled ‘BILDERLISTE MIT PREISSCHAETZUNGEN’, there are 40 paintings and drawings including a ‘Landschaft’ by ‘Kandinsky’, stating the country as ‘USA’ and an estimated value of ‘[DOLLAR] 500.-’. This list gives the country as ‘USA’ and estimated values in dollars for eleven other works. The work by Kandinsky is the only one on the ‘Bilderliste’ to have been crossed out by hand. All 40 paintings and drawings on the ‘Bilderliste’, with the exception of three paintings including the painting by Kandinsky, are referred to on an expert’s certificate issued by Houthakker on 18 September 1952 that concerned 37 paintings ‘behorende tot de nalatenschap van Mevrouw M.J. Stern-Lippmann en zich bevindende in diverse percelen te Nunspeet (Gld.) en te Amsterdam in het Stedelijk Museum en in het gebouw van de Associatie Cassa‘ [‘belonging to the estate Mrs M.J. Stern-Lippmann and that are present in various properties in Nunspeet (Gelderland) and in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and in the Associatie Cassa building’].

Apart from the aforementioned ‘Bilderliste’, there is no mention of a painting by Kandinsky on the other lists of valuations found in Houthakker’s archive. The name is also not referred to in the other documentation found after the liberation.

Paintings from the Stern-Lippmann collection were still missing after the division of Stern-Lippmann’s estate in 1954. This emerges from a letter from the financial and legal advisor W.H.C. Schukking of 12 May 1955 to the SNK, which was subsequently closed down. Enclosed with this letter was a list of 28 artworks headed ‘Schilderijen van wijlen Mevr. Marg. Stern-Lippmann, welke na 1945 niet meer in de boedel werden aangetroffen‘ [‘Paintings of the late Mrs Marg. Stern-Lippmann that after 1945 were no longer found in the estate’] (hereinafter also referred to as the Schukking list). It is stated in the letter that it concerns works that belonged to Stern-Lippmann in 1940. No work by Kandinsky is mentioned on the Schukking list. Similarly no work by Kandinsky is referred to on the 1958 list of missing artworks that was sent in 1959 to the Wiedergutmachungsämter von Berlin (WGA), which corresponds largely with the Schukking list. The WGA file contains a statement by Schukking stating that the sums accompanying the artworks concerned were taken from insurance policies dating from the 1934-1938 period.

3.5 The currently claimed work was purchased by the Museum in 1951 from the art dealer Karl Alexander Legat in The Hague. The following handwritten provenance information is noted on one of the painting’s inventory cards submitted by the Museum. ‘Légat, Den Haag (1951) f. 11.500-’; ‘Vroeger verzameling A. Kaufmann; door diens in Nederl. wonende dochter verkocht Légat. (opg. Légat)’ [‘Légat, The Hague (1951) f. 11.500-’; ‘Previously the collection of A. Kaufmann; whose daughter living in the Netherlands sold it to Légat. (stated by Légat)’]. It can be deduced from correspondence about the purchase in 1951 that Legat had paid NLG 10,000 for the work. It is not clear who ‘A. Kaufmann’ refers to.

Previously, in 1949, Legat had offered the Museum another work by Kandinsky, Kirche in Murnau. In the end this work did not go to a Dutch museum but was acquired in 1950 by the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Before that, the work was submitted by Legat for the exhibition Expressionisme: Van Gogh tot Picasso [Expressionism: Van Gogh to Picasso], which was staged in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam from July to September 1949. The currently claimed work was not on display in that exhibition.