IV – The facts

IV.1. Koenigs was born in Kierberg, Germany, on 3 September 1881. In 1920 he founded N.V. Rhodius Koenigs Handelmaatschappij together with a nephew. The business was established in Amsterdam. A few years later Koenigs and his wife Anna Countess of Kalckreuth (hereinafter referred to as Anna Koenigs) and their children moved permanently to the Netherlands. Neither of them was of Jewish descent. Koenigs was granted Dutch citizenship in 1939.

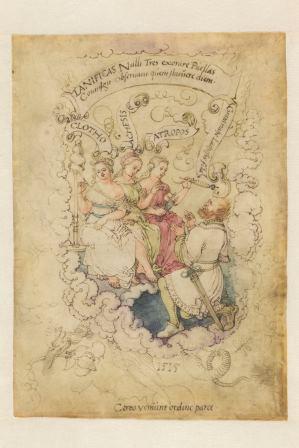

IV.2. During the nineteen-twenties Koenigs started what was to become a large collection of drawings and paintings. The collection of drawings, also known as the Koenigs collection, was of art historical importance.

IV.3. It can be deduced from a declaration that Koenigs wrote by hand and signed on 9 September 1931 that he entered into an agreement with the Amsterdam bank N.V. Bankierskantoor Lisser & Rosenkranz (hereinafter referred to as L&R). He was friends with S. Kramarsky, the Jewish managing director. In the declaration Koenigs wrote to L&R: ‘Sie haben mir namens einer Gruppe zugesagt an der Capital erhöhung von Rhodius Koenigs Handel Mij im Ausmass von fl. 1.500.000,- mitzuwirken’. He also wrote that he was transferring ownership of his drawing collection, as present in his home in Haarlem, to L&R as security for repayment. The agreement between Koenigs and L&R was probably formalized a few weeks later by, among other things, a legal instrument dated 2 October 1931, the contents of which are not known to the Committee.

IV.4. A new agreement between Koenigs and L&R was recorded in a registered private legal instrument dated 1 June 1935, in which it was expressly stated that the old agreements lapsed. This document was not available to the Committee when the advice with regard to RC 1.6 was formulated. It was submitted in 2008 by Koenigs’s son FF as part of the RC 1.35 procedure. It states that Koenigs acknowledged borrowing a sum of NLG 1,375,000 and GBP 17,000 at an interest rate of 4% for a term of 5 years. Under the agreement, Koenigs transferred ownership of his drawing and painting collection, as specified on a list accompanying the legal instrument, to L&R. The list, which according to the text must originally have been appended to the legal instrument of 1 June 1935, is currently missing, but it is clear from the text of the agreement that the paintings and drawings concerned had been lent shortly beforehand to Museum Boymans in Rotterdam and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Koenigs and L&R furthermore agreed that Koenigs was entitled to repay part or all of the loan at any time, while L&R would be entitled to sell the collection publicly or privately and to recover the proceeds upon expiry of the term (31 May 1940) or upon the liquidation of L&R.

IV.5. Starting in 1939, close to the expiry of the agreed term and under the growing threat of war, Koenigs and the L&R bank, through the mediation of art dealer Jacques Goudstikker, conducted negotiations with Dirk Hannema, director of Museum Boymans. It can be deduced from the correspondence that apparently Koenigs’s objective was to house the drawing collection as one entity, under his name, permanently in Museum Boymans. The wealthy Rotterdam businessmen D.G. van Beuningen and W. van der Vorm were involved in the discussions as financiers. Koenigs kept other interested parties at arm’s length. It can be concluded from a letter drafted by Jacques Goudstikker in around February 1940 and intended for Hannema that Koenigs was prepared to make far-reaching concessions in order to ensure that the collection continued to be retained for the museum. But the negotiations broke down. Meanwhile Koenigs and L&R made plans to transport the collection abroad.

IV.6. L&R was liquidated on 2 April 1940. The intention was to safeguard the bank, which had a mainly Jewish board, from German interference in the event of a German attack. Koenigs, who was present as a fellow shareholder at the meeting of shareholders in which it was decided by acclamation to do so, would have been closely involved in the development and further implementation of the plans.

IV.7. It is stated in two registered private legal instruments of 2 April 1940, which were co-signed by Koenigs, that as of 2 April 1940 Koenigs had a debit balance in the current account relationship entered into between him and L&R, including interest, of NLG 1,662,915.14 in addition to GBP 20,559.13s.7d. These two instruments were also not available to the Committee during its formulation of advice for RC 1.6. They were handed over by FF in 2008 in connection with RC 1.35.

IV.8. It is stated in the first instrument, which is a further agreement about the main part of the debt and the drawing collection, that the ‘parties have been consulting each other about partial settlement of Koenigs’s debt to Lisser & Rosenkranz’ and that the parties have agreed the following in this regard: ‘As partial settlement of his said debt in the amount of NLG 1,250,000.-, Koenigs gives Lisser & Rosenkranz as payment, and the latter herewith accepts as payment, the collection of drawings that has been lent by Koenigs to Museum Boymans in Rotterdam, as accurately specified on the list attached to the aforementioned instrument of 1 June 1935 and authenticated by both parties. Koenigs therefore herewith transfers the full and unencumbered ownership of the said drawings to Lisser & Rosenkranz, and Lisser & Rosenkranz accepts this transfer of ownership, in return for which it discharges Koenigs from NLG 1,250,000.- of his said debt.’

IV.9. It is stated in the second instrument, which is a further agreement relating to the paintings, that the ‘parties have been consulting each other about the settlement of Koenigs’s remaining debt to Lisser & Rosenkranz’ and that the parties have agreed the following in this regard: ‘As settlement of his residual said debt in the amount of NLG 412,915.14 and GBP 20,559.13s.7d, Koenigs gives Lisser & Rosenkranz as payment, and the latter herewith accepts as payment, the paintings as accurately specified on the list attached to the aforementioned instrument of 1 June 1935 and authenticated by both parties. Koenigs therefore herewith transfers the full and unencumbered ownership of the said paintings to Lisser & Rosenkranz, and Lisser & Rosenkranz accepts this transfer of ownership, in return for which it discharges Koenigs from the aforementioned residual of his said debt.’

IV.10. It emerges from surviving correspondence that L&R and Koenigs each separately informed Museum Boymans that same day that the drawing collection had become the property of the L&R bank. Koenigs also wrote that, in view of the absence of a response from the museum, it had been necessary for him to use the drawings as payment, as a result of which the drawings had become the ‘full and unencumbered property’ of L&R, and that he had made the drawings completely available to L&R ‘in so far as necessary by terminating the loan of them to you’. L&R advised the museum that it intended to have the drawings removed that same week by the forwarding agent.

IV.11. There was further consultation after 2 April 1940 between L&R ( represented by Jacques Goudstikker), Museum Boymans ( represented by its director Dirk Hannema) and D.G. van Beuningen. A surviving letter of 9 April 1940 from Hannema to L&R reveals that Koenigs was also present at these discussions. L&R continued to take Koenigs’s wishes into account after 2 April 1940, as can be seen from a letter to Goudstikker from L&R dated 8 April 1940: ‘Please bear in mind that we want to make the greatest possible concession to Museum Boymans as regards the price on the grounds of both national considerations and our desire to respect the wishes of the previous owner [Koenigs, RC].’

IV.12. On 9 April 1940 L&R sent written confirmation to Van Beuningen that it had sold him the drawing collection as well as 12 paintings for NLG 1 million. In the letter L&R wrote: ‘We have noted with thanks your promise that the aforementioned collections of drawings and paintings will continue to bear the existing name of the “F. Koenigs Collection” for as long as they remain exhibited in Museum Boymans.’

IV.13. This was followed by congratulations all round. The board of L&R expressed its satisfaction about the fact it had been able to contribute to ‘the retention of this important collection for the Netherlands and Museum Boymans’. The undertaking by Van Beuningen to keep the name of Koenigs linked to the collection ‘also fulfilled the wish of Mr Koenigs’, added L&R. On 12 April 1940 Hannema assured Koenigs ‘that the collection, with which your name will always be associated, will also be looked after with the greatest care in the future’. On 17 April 1940 Koenigs wrote to Hannema saying that: ‘We are also pleased that the collection has remained in Holland and naturally we prefer to see it in Museum Boymans’. As an expression of his feelings, Koenigs donated two drawings by Carpaccio to the museum to supplement the collection. On 19 April 1940 Hannema wrote to L&R saying he was happy that ‘the entire Koenigs collection…is staying in Museum Boymans’ and he thanked the L&R bank’s board for the cooperation.

IV.14. In his biography of D.G. van Beuningen, Harry van Wijnen (p 317) writes that on 28 April 1940 – a few weeks after the transaction between L&R and Van Beuningen on 9 April 1940, but still before the German invasion – there was an exploratory meeting in The Hague between Van Beuningen’s son-in-law, Lucas Peterich, and the German Dr Hans Posse, who purchased art on behalf of Adolf Hitler for the Führer Museum that was to be established in Linz. On 5 August 1940 Peterich reminded Posse of this discussion in a letter. In it he stated that at the time he assumed that his father-in-law did not want to sell anything, but ‘so glaube ich heute, daβ er jetzt vielleicht doch dazu bereit sein würde, wenn Sie ein gutes Angebot auf die Zeichnungen der Sammlung Königs machen könnten’. During the course of the following months Peterich negotiated with Posse on behalf of Van Beuningen about the purchase of part of the drawing collection.

IV.15. At the beginning of December 1940 Van Beuningen sold some 528 drawings to Posse for NLG 1.4 million. On 9 December 1940 Hannema told a member of the board of trustees of the Museum Boymans Foundation about this sale, namely that, ‘Mr van Beuningen had had a plan to sell for a certain sum of money a part of the Koenigs collection, which he had acquired before the war. This transaction has already taken place’. Some 37 of these drawings were recovered after the war and at the end of the nineteen-eighties they were sent back, primarily from the former German Democratic Republic, after which they became part of the NK collection. These 37 drawings are subjects of the current advice. Van Beuningen donated the other drawings, numbering approximately 2,000, and eight paintings to the Museum Boymans Foundation.

IV.16. The paintings that were not part of the agreement of 9 April 1940 between L&R and Van Beuningen were removed from Museum Boymans by Goudstikker. It is uncertain where these works were taken. It is also not clear whether further agreements about these works were made between Koenigs and L&R after 2 April 1940 and, if so, what their import was. In a letter dated 10 December 1946, that was handed over by the applicant in regard to the current request, L&R wrote that on 1 May 1940 it had 35 paintings in its possession for Koenigs, while Koenigs owed the bank NLG 706,088.47 plus GBP 20,559.13s.7d, adding up to a total of NLG 844,557.87. This letter then summarizes the works concerned. Number 14 is Cadmus Sowing the Dragon’s Teeth by P.P. Rubens, the work currently being claimed. It is stated in the letter that this painting was handed over on the instructions of Mr F. Koenigs for NLG 11,600. It emerges from surviving documentation that Cadmus Sowing the Dragon’s Teeth was then sold at the end of April or beginning of May 1940 to a Dutch couple, Mr and Mrs De Bruijn, through the J. Goudstikker gallery. Goudstikker gave the proceeds to L&R. This work of art was bequeathed to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam in 1961, thus becoming part of the Dutch National Art Collection.

IV.17. In its letter of 10 December 1946 L&R also stated that 31 paintings were handed over for NLG 800,000. On an unknown date, probably in June 1940, they were purchased by the German banker Alois Miedl. Twenty-seven of these 31 paintings are subjects of the current advice. A report written in 1952 by the lawyer A.E.D. von Saher entitled ‘N.V. Kunsthandel J. Goudstikker: overview of events during the period from 31 December 1939 to April 1952’ says about this sale that, ‘In June 1940 Miedl bought Koenigs’s Rubens collection from him for NLG 800,000’. A post-war report about the Miedl hearings states the following. ‘The sale took place in the garden of the Lisser Rosencranz Bank in the presence of Florsheim, the deputy director in the absence of Kramarsky who had left for America…Koenigs at first asked 800.000 and finally accepted 700.000. Miedl admits that this was very cheap but says Koenigs was no Jew and was eager to sell to clear himself of his financial obligations because the banks in Holland would not take pictures as security…Koenigs was actually paid 800.000 gulden by Miedl, and Flörsheim supplied the difference.’

IV.18. After this there were various further business contacts between Koenigs and Miedl. On 14 September 1940, in the presence of the notary A. van den Bergh in Amsterdam, the firm of ‘Kunsthandel voorheen J. Goudstikker N.V.’ was founded. Alois Miedl traded art during the war through this company. Koenigs was one of the founders besides Miedl. He participated in the issued capital by purchasing five of the 600 shares. Miedl’s bank, N.V. Buitenlandsche Bankvereniging (BBV), also acquired a substantial number of L&R shares in the course of 1940. Op 13 December 1945 H.H.F. Herrndorf, one of L&R’s liquidators, said the following about this matter. ‘As a very good friend, Mr Koenigs felt obliged to champion the interests of L&R and to actually protect it. The relationship with and the friendly feelings for L&R. resulted in Rhodius Koenigs buying 540 shares from Mr F [Flörsheim, RC] on 9-9-’40 at 75 %. By then it was clear to Mr Koenigs that his position was not strong enough to protect L&R properly. The upshot of these considerations, together the general situation, was the acquisition of the shares by BBV…As a consequence of the steps that had already been taken, it seemed necessary to Mr Koenigs that the 687 shares of Mr S. Kramarsky should also change hands. He was convinced that this would be the best way to serve the interests of his friend Kramarsky, and the consequence was that BBV took over L&R.’

IV.19. Koenigs died on 6 May 1941 at a railway station in Cologne, Germany.

IV.20. In May 1942, a year after Koenigs’s sudden death, his widow Anna Koenigs wrote to Hannema saying, ‘I’m glad about everything that stayed in Museum Boymans and in the Netherlands, because it was always my husband’s wish that his collection should remain in our country.’ In response to a declaration obligation announced by the authorities, after the war Anna Koenigs filled in 31 SNK (Netherlands Art Property Foundation) declaration forms, in which she reported the sale of 31 paintings by Koenigs to A. Miedl in the ‘summer of 1940’. There was a pre-printed line for declaring the nature of the loss of possession: ‘As a result of confiscation / theft / forced/voluntary sale, it came into the possession of’. She crossed out the first three options, and in so going declared that according to her it was a voluntary sale.

IV.21. A few years after the war one or more of Koenigs’s heirs apparently had an investigation carried out in order to establish whether Van Beuningen could be called to account for reselling works from the collection to Posse. At the time the idea was dropped because of negative legal advice to the effect that ‘the agreement concerned [between L&R in liquidation and Van Beuningen, RC] created legal relationships between Mr van Beuningen and the aforementioned N.V. only, and a possible promise to preserve the Koenigs collection and to continue the loan to Boymans Museum does not have the character of a third-party clause, the fulfilment of which could be enforced at law by the heirs’ (letter from the lawyer Max Meijer to FF of 19 August 1953).